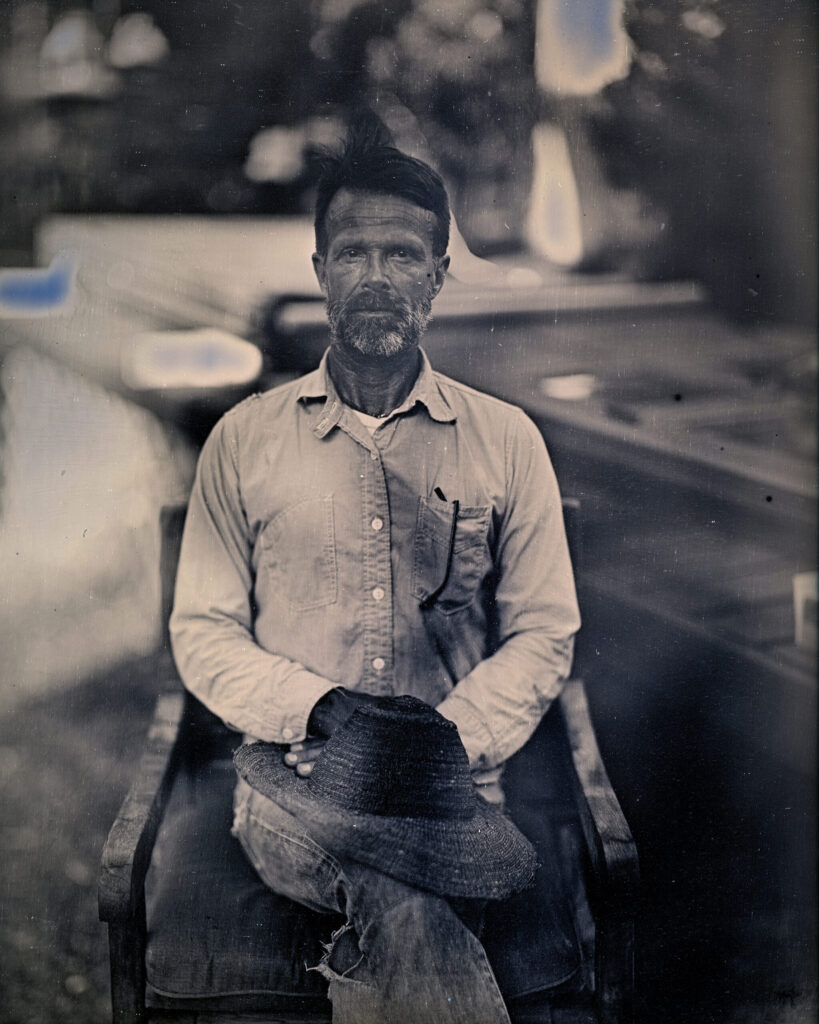

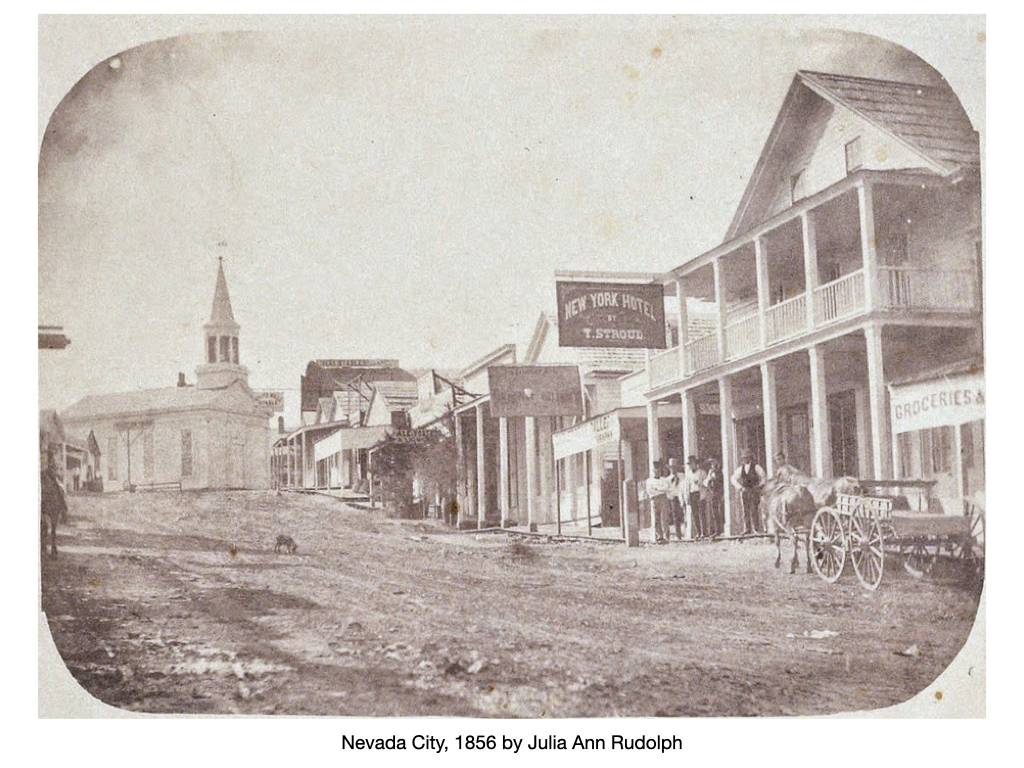

Nevada City was first settled in 1849 as a mining camp during the California Gold Rush. By 1850–51, it had become the most important mining town in the state. In 1856, photographer Julia Ann Rudolph—Nevada City’s first woman photographer—opened a studio on Broad Street, offering “all the latest instruments and chemicals,” (1) including daguerreotypes, and later ambrotypes, tintypes, and albumen prints. She specialized in studio portraits but also captured scenes of everyday life on the street. Inspired by Rudolph’s work, I turned to these early photographs of Nevada City as a point of departure for my own rephotographing project.

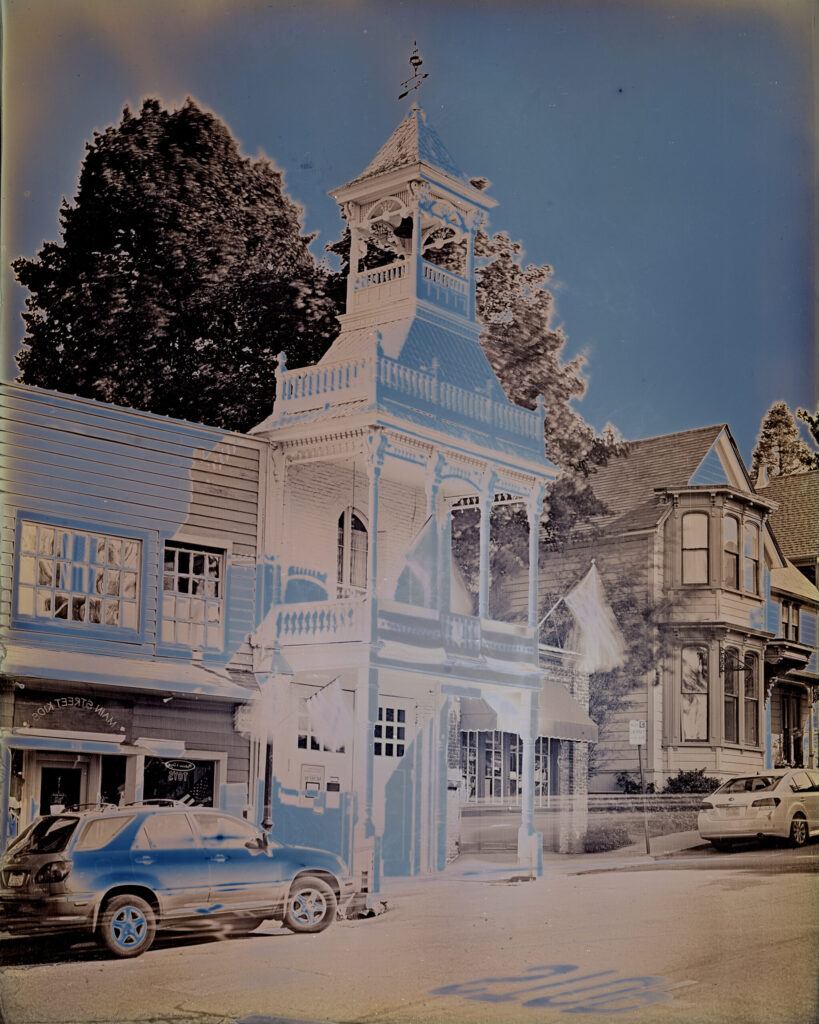

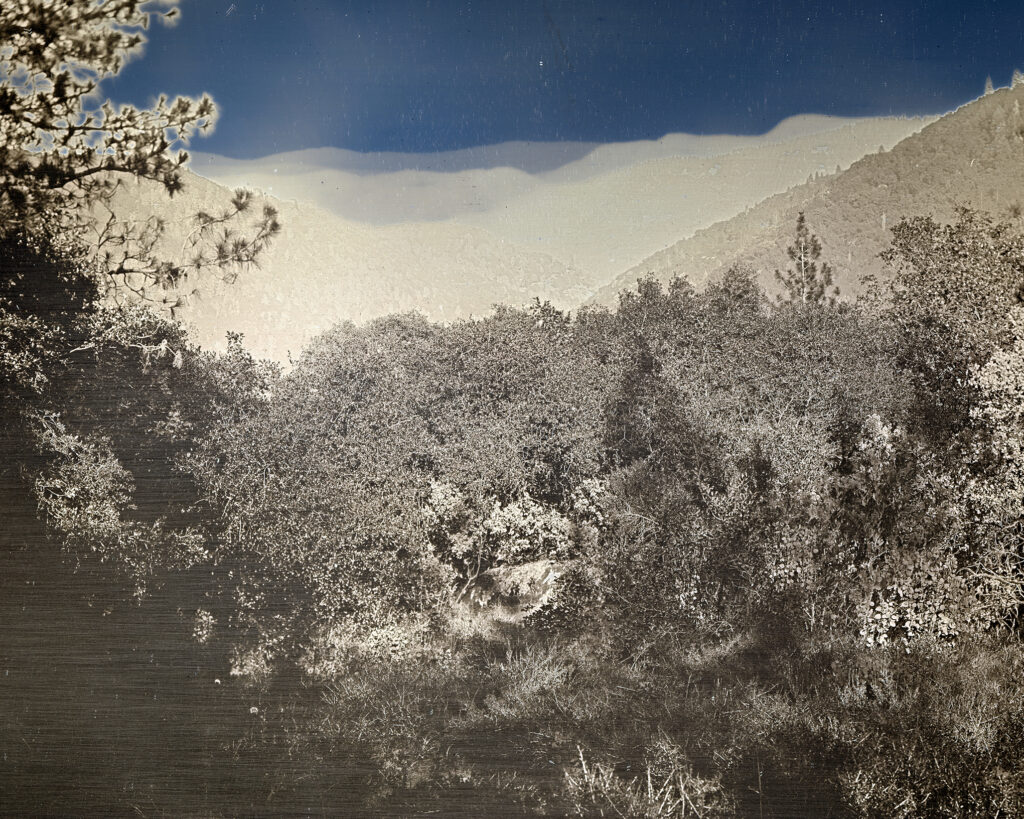

After Congress banned hydraulic mining in 1884, Nevada County had already earned a reputation as one of the most environmentally damaged places on earth. Yet nearly a century later, in the 1960s and ’70s, the area was rediscovered by the “back to the land” movement—a kind of second gold rush centered on nature, community, and a deeper connection to place. Today, Nevada City stands as one of Gold Country’s most charming towns, with a well-preserved historic core that includes landmarks like the bell-towered firehouse on Main Street, adorned with Victorian gingerbread detailing. The local history museum houses not only relics from the town’s early settler days and Chinese pioneers but also the intricate cooking baskets made by the native Nisenan people, whose presence long predates the gold rush.

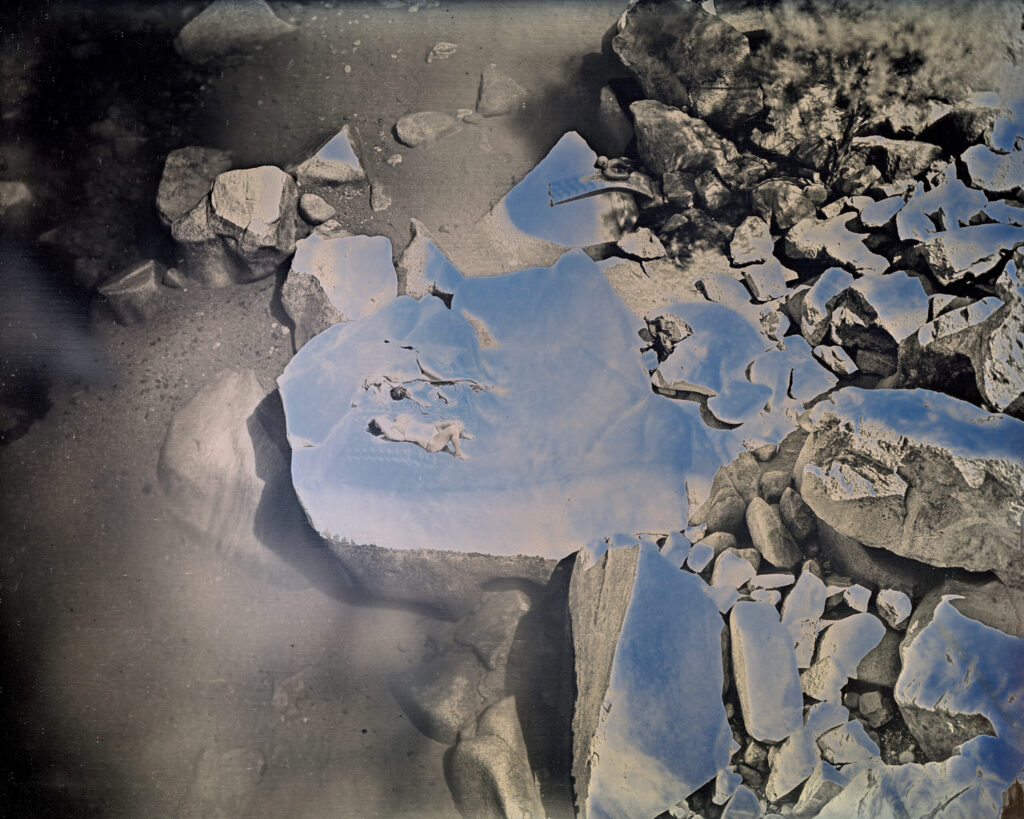

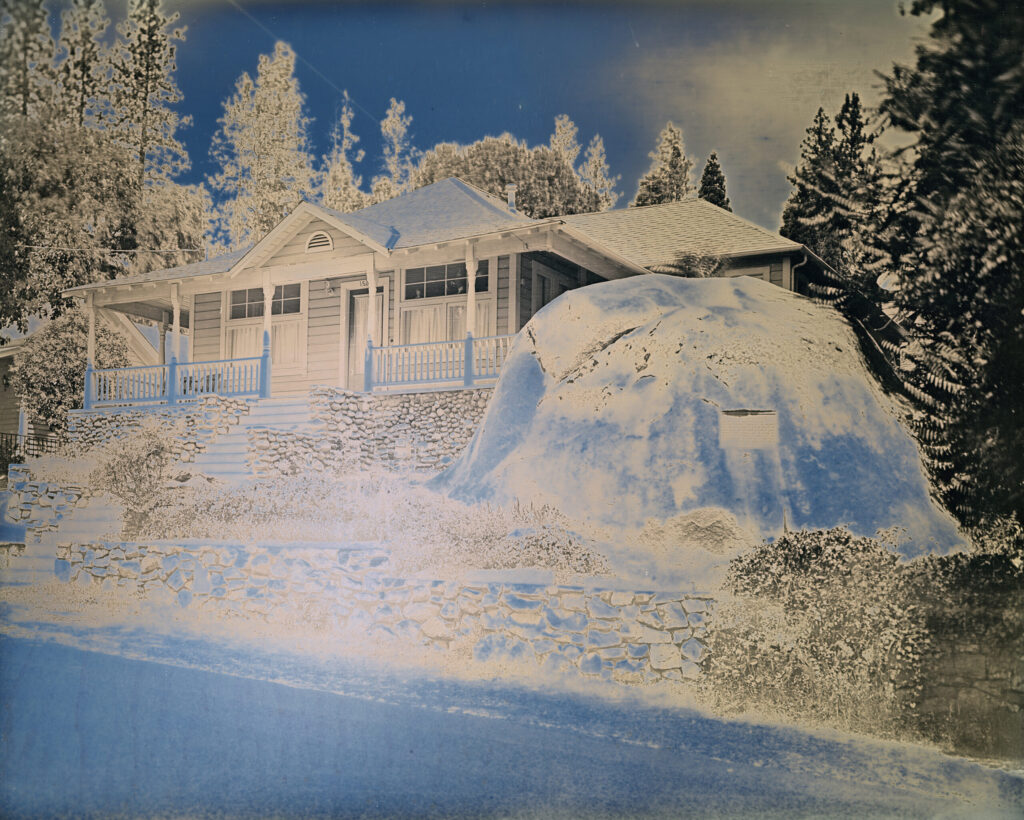

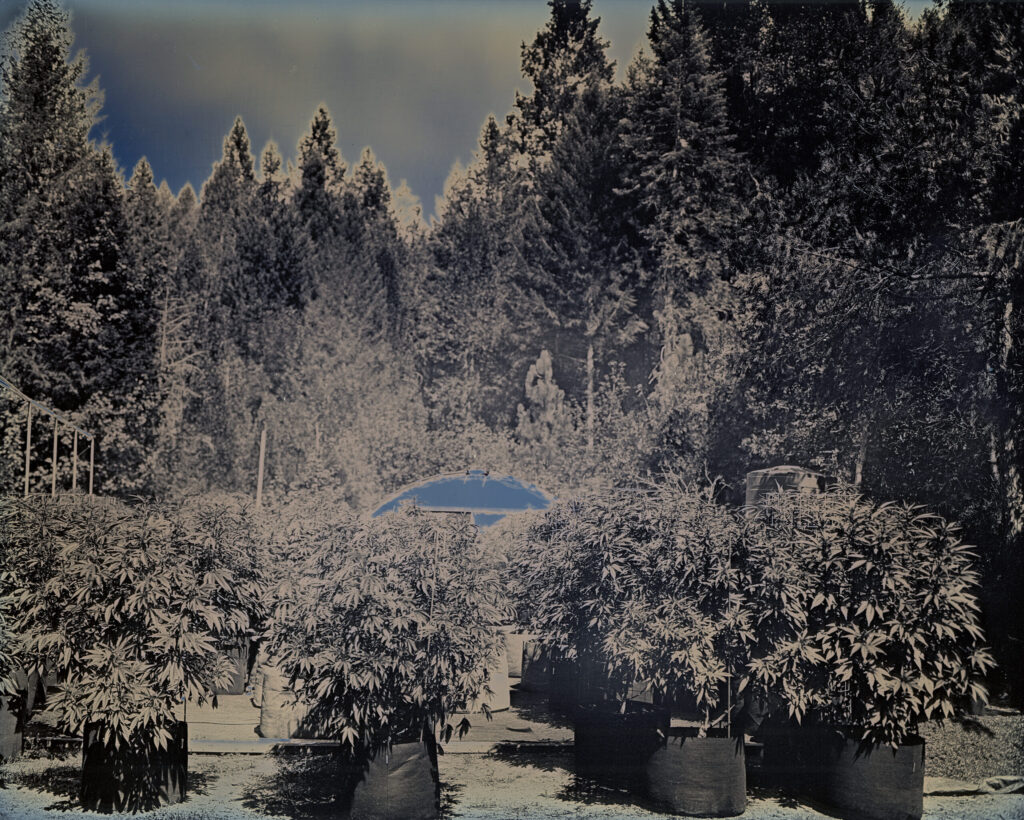

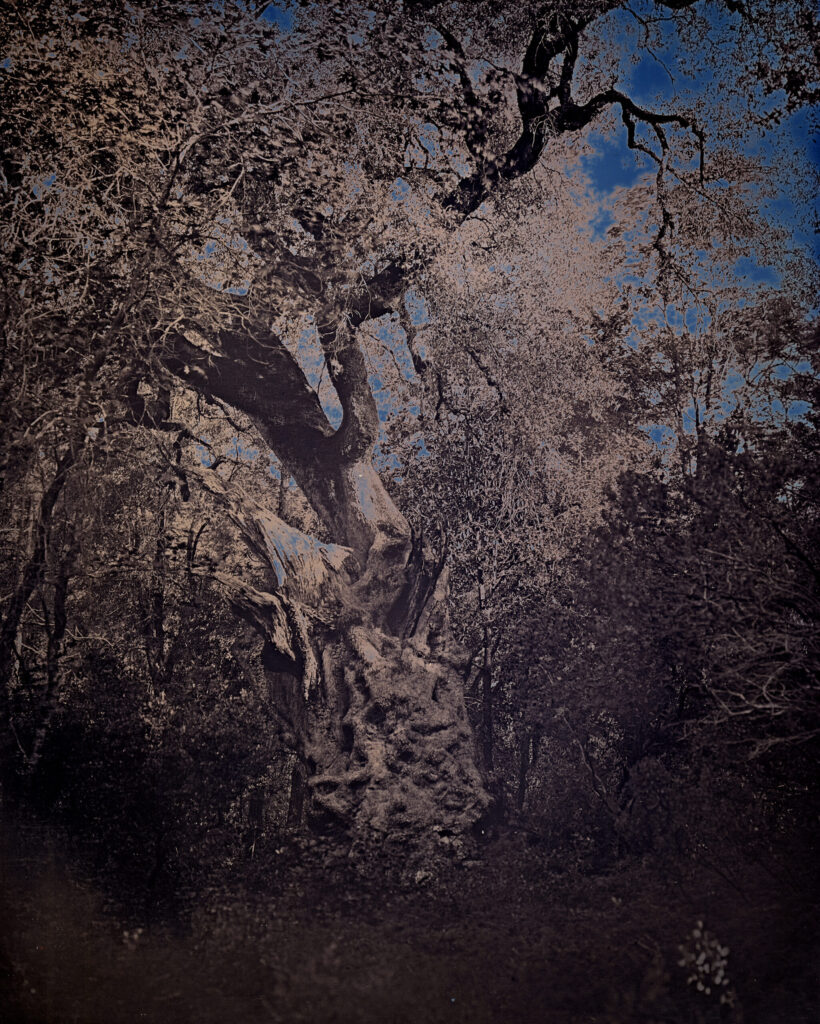

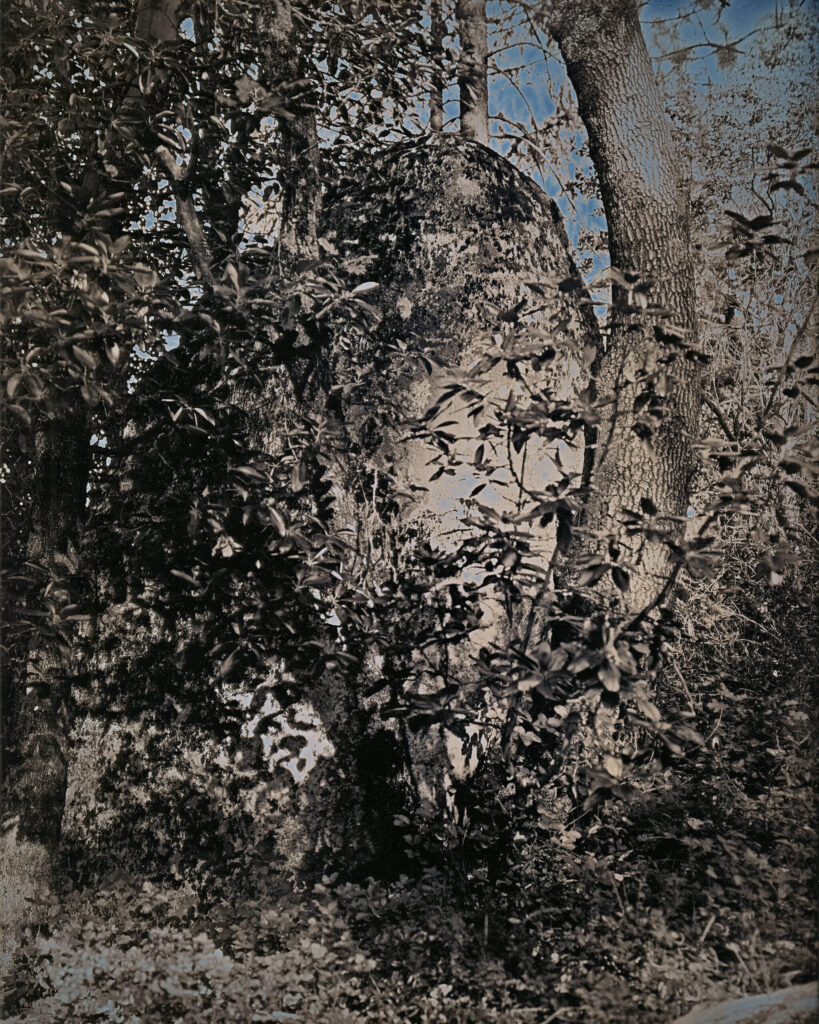

As I worked on this project, I kept asking myself: What is Nevada City today? A weekend escape? A town of preserved buildings and forgotten Native American sites? A landscape marked by old mines and pioneer cemeteries? A river town where sunbathers and swimmers lounge by the South Yuba near an abandoned miner’s tunnel? A hub for farmers growing both organic produce and cannabis—a modern-day “green rush”? A place that overlooks the deep gorge of the South Yuba River, layered with history?

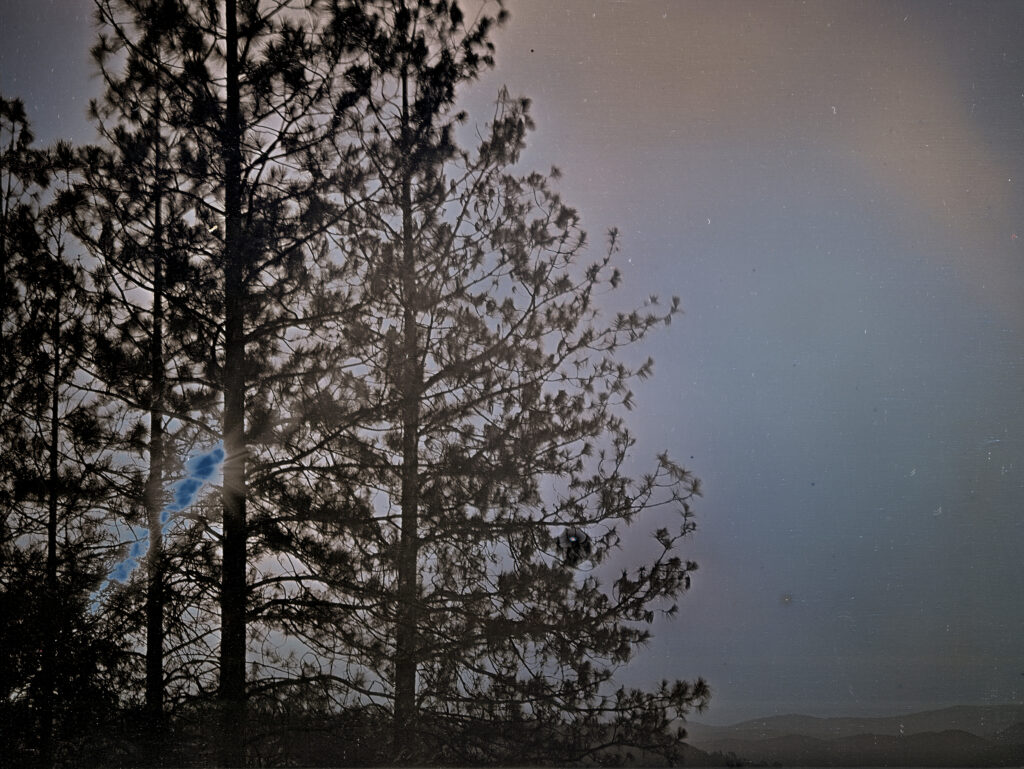

The daguerreotype, as a medium, lets us reflect—literally and metaphorically—on the layers of time. These images are formed by light bouncing off the landscape, chemically fixed on silver-iodine plates, developed in mercury fumes, and gilded in gold chloride. Beneath the vines, the bricks, the wood, the tombstones, the roots, the rocks, and the remnants of lives once lived, lie deeper truths. Within the mirror-like surface of the daguerreotype, we see not only the image but also ourselves—our skin, our histories, our imaginations, our hopes and longings.

1) Palmquist, Peter E., and Thomas R. Kailbourn. Pioneer Photographers of the Far West: A Biographical Dictionary, 1840-1865. Stanford University Press, 2000, pp. 463–64.

Daguerreotype plate sizes are “full” and “8 x 10” inches.